Spotlight: Distant-Reading and Visualization

*Thank you to Allie Watson (@allieisanant) for her collaboration on this piece.

Introduction

This article approaches methods of analysis to the study of literature using big data. In the study of literature, the method of close reading is historically privileged. Close reading entails examining a small piece of a text to analyze the mechanisms of form and style, thus drawing conclusions about the specific workings of the text. For example, what is the significance of a run-on sentence in a moment of crisis for a character? What can be drawn from this passage when understanding the themes of the text as a whole?

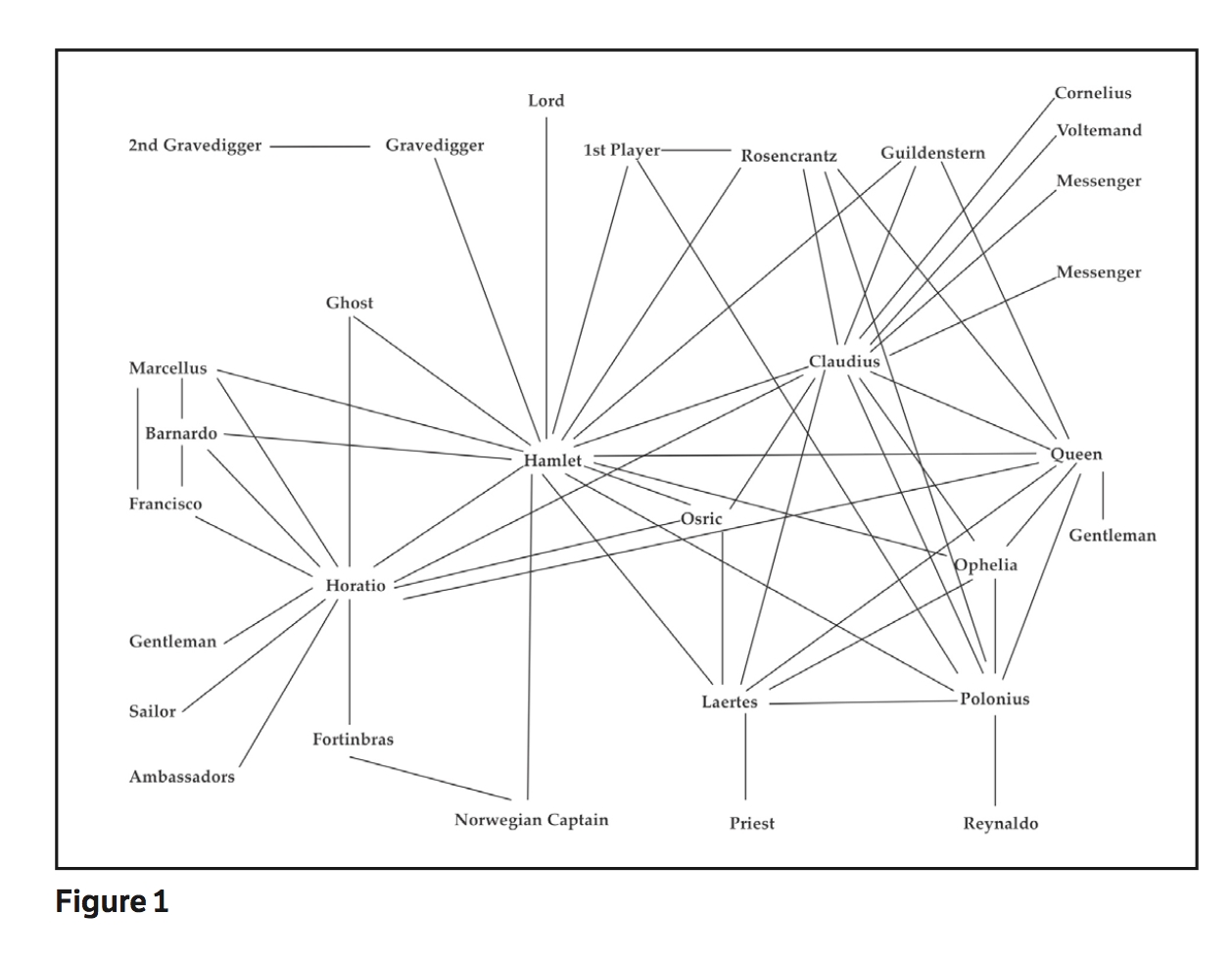

With the development of humanities computing, some literature scholars have moved away from the traditional means of close reading towards distant-reading. This shift means that instead of focusing on a single section of a single text, scholars can expand their vision to categorize, analyze and even visualize literary works. It allows them to draw together data from hundreds or even thousands of different texts and identify trends and networks within those collections. The Stanford Literary Lab Stanford Literary Lab, lead by Franco Moretti, is one such group working on the mathematical collection and subsequent analysis of literature. For example, their current ongoing projects include a model of the networks in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the mapping of algorithms in the historical development of English poetry, and creating an emotional map of London, in which they trace the locations of great emotion in British texts of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Though some scholars still cling to the old supremacy of close reading, distant reading can still tell us a lot about the historical and literary trends which inform our understanding of literature.

One core criticism of distant reading is its collectivity in mapping several texts, which critics argue causes scholars to neglect non-canonical texts into group collectives instead of allowing them due study. This is particularly relevant when considering long-ignored texts featuring marginalized voices. However, we argue that distant reading can highlight important patterns in these texts and thus draw them to critical attention. Understanding a text’s placement in the larger literary context and its relations to others of the genre or author tells us much about the texts.

Visualization

What is the impact of visualization when it comes to literature? Why bother turning information about texts into a graph or display, some of which contain so many vast amounts of data that the names of the nodes become invisible or obsolete? The shift towards distant reading requires the scholar to take a distanced perspective: to look at the texts as a whole, as numbers falling into several patterns, not at the specific relationships between certain data. In Moretti’s article “Network Theory, Plot Analysis,” he explains that this shift can be difficult to conceptualize. In his visual displays of Hamlet, for example, he says “nothing about Shakespeare’s words – but also, in another sense, much more than it, because a model allows you to see the underlying structures of a complex object” (4). This is significant when studying the enclosed world of the plot of a play. It is also relevant when understanding broader literary connections within a certain genre or era.

The genre and era we have chosen for analysis is a dataset of children’s literature published in the nineteenth-century, featuring basic information about 234 texts and their authors. We chose this data set for a few reasons. Firstly, this era of children’s literature is frequently understudied, with the exception of a few popular works which have received attention.

Jane Bingham and Grayce Scholt argue that in the eighteenth century, children’s books were seen as being for instruction and moral guidance, saying “much good ink and paper was expended in persuading children of the profits of virtuous behavior” (68). However, events such as the translations of the Grimm brothers coming to England and a rise in print culture in the nineteenth century spurred a change in attitudes. With the growth in popularity of the European fairytale, children’s literature began to be less about teaching (or threatening) the virtues of morality and more about entertainment and consumption. With a growing industrial middle class and increased literacy, print technologies maximizing the number of books that could be printed and the circulation of mobile libraries which spread literature to greater amounts of urban and rural populations alike, children’s literature gained significance, further positioning the child as an individual subject and parallel consumer of both literature and culture.

The data was collected by students in Alan Liu’s English 197 course at the University of California, Santa Barbara Check it out here. It features over two hundred children’s books published in the 1880’s.

Paradata

What choices were involved in the making of this visualization? Firstly, the original dataset came with several categories:

ID

Title of Book

Author’s date of birth

Author’s date of death

Author’s full name

Author’s first name

Author’s last name

Author gender

Author nationality

Genre

Source

Year published

Word Count

chunks

chunked?

Notes

In order to create a coherent and informative visualization, we chose to focus on a few specific categories.

Author’s gender: Author gender has been significant to literary study of the nineteenth century. Not only was this a century which saw great change and women’s activism, literature reflected the discourses upon which gender was talked about in society. For example, Charles Dickens was a known advocate for ‘fallen women,’ and books such as David Copperfield were designed to emotionally move the contemporary reader into sympathy that might affect social attitudes and change. Furthermore, the novel was often generalized as being feminine in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, while poetry was believed to be masculine and a higher form of literature. Novel-reading and writing slowly began to gain authority as a masculine activity after the publication of famed poet Sir Walter Scott’s historical novel Waverley. However, what is the impact of author gender on children’s literature? We are looking at novels from the late nineteenth-century, when novels had moved away from being purely instructive to about entertainment. Can we draw any conclusions when examining the author’s gender of these texts?

Author’s nationality: Assuming that this collection of data is somewhat comprehensive, what does the nationality of the author say about the market of the nineteenth century? This question raises larger issues: for example, what is considered to be British literature? Is the mere categorization of the author’s nationality enough to justify? For this dataset, the nationalities are: English, Scottish, Irish, American, and one from Switzerland – the beloved classic, Heidi. It is a shame that the dataset does not include statistics of how popular the novels were, how much money was raised, or how far they were circulated, as this information could lead us to conclusions about hierarchies of the author’s nationality: at the time, Irish literature was devalued, and the English have often claimed Irish authors as their own, Oscar Wilde and Jonathan Swift being examples.

Word Count: The third aspect of the data that we chose to analyze was the word count of each text, to see if there would be any trends. Do female writers produce more words than their male counterparts? Are English writers less likely to create huge volumes of text?

The other categories might be useful for another study, and neglecting them deserves some inspiration. Some, such as Source (which was all Project Gutenberg), are obvious choices for omission. The names of the authors are more relevant to close reading and the analysis of one or two texts: what is more significant is the data about the authors, such as gender and nationality. The year of publication is less relevant because the data samples all come from the same decade; however, they might be relevant if compared with specific literary or political events of the decade. Visualization is general.

Visualizing Voice

For the visualization of this data, we used an online program called RAW. RAW In the following section, we will describe our process of creating the visualization and justify our choices.

The form of chart we chose is called a Clustered Force Layout. According to the RAW website, these are effective to “show the proportion between elements through their areas and their position inside a hierarchical structure” (RAW). The layout is bright, pleasing, and simple.

This suspense is terrible. I hope it will last. -Oscar Wilde

However, without further ado, here is our visualization:

Each of the three categories we focused on was arranged into a certain string, which determines the layout of the visualization.

Nationality—Cluster: The four prime nationalities of the authors each correspond to the clusters of the nodes, as you can see above. The largest one, which is on the left, represents authors from England, while the two medium-sized clusters represent Scotland (bottom right) and America (top right). The small cluster at the top depicts the authors of Irish nationality. The method used here was poetically perfect for the visualization, as it literally maps the authors onto a visualized instead of a geographical space.

Gender—Colour: The pale blue nodes represent male authors, and the dark purple nodes represent female authors. This is an easy way of distinguishing the genders of the authors and observing if there are patterns between gender and the other strings. We tried to choose colours which would be still distinguishable to colour blind readers.

Size—Word Count: This one is easy. The larger the node, the longer the text.

Analysis

What story does this visualization tell?

Firstly, the clusters of the nationalities are very telling about the hierarchies of this literature. The largest cluster represents authors born in England, demonstrating privilege on the basis of nationality. Interestingly, Ireland has a very small cluster of nodes, and perhaps this is due to the history of the relationship between England and Ireland as it existed under English rule. The Irish existed in the poles of those who were “within the pale,” the walled city of Dublin where the English-Irish lived, spoke and wrote in English and practiced English Protestantism, and those who were “beyond the pale,” the rural, indigenous Irish who spoke Gaelic and practiced Catholicism, and were as a result greatly marginalized and prosecuted for their language and religion on their own land. In the context of literature, the visualization suggests how Irish voices are pushed to the side in the wake of the greater bulk of English voices circulating through society.

Secondly, the binaries of gender are represented through the two colours. It is immediately obvious that there are more male writers of children’s literature publishing in the 1880’s than female. We have already discussed the gendering of literature in the era. Perhaps this says something about whose voices were held responsible and authoritative. Arguably, male writers were taken more seriously than women, and perhaps this shows the serious nature of children’s literature and it’s role in society. The marginalizing of female voices can thus be assumed from this particular visualization.

Furthermore, there appear to be more female writers emerging from America than from England and Scotland, the latter having only one node identified as female. Meanwhile, all of the Irish writers are female. Also, in England especially, women are shown to be writing shorter texts than male writers. Americans in general write shorter texts than English and Scottish writers.

Conclusions

There is something beautiful about this image in how it visualizes voice. It draws attention to the literary hierarchies of the 1880’s: whose voices were being circulated? It also grants us the chance to express initial reactions and observations when these hierarchies are laid out in front of us in easily interpretable methods which we can understand.

But this method of visualization also equalizes the individual authors. In not considering fame, capital or amounts of production of certain texts, forgotten authors are just as important as the famous ones. Race becomes invisible through these sorts of analyses, unless they are integrated into the strings. However, we do believe that these are important hierarchies which need to be deconstructed as well.

Moving forward, we conclude that this method of visualizing literary trends has the potential to be incredibly useful. We foresee a time when close reading and distant reading can come together through these analyses to relate larger trends to individual works and the words within them.

On Accessibility

One concern with all digital media and communication is the content’s accessibility. Our ultimate goal when designing and communicating is to be accessible to all consumers, no matter their disabilities or special needs and requirements when processing web data. The article “Disability, Universal Design, and the Digital Humanities” by George Williams argues for the benefits of accessible digital spaces. He says that in the future, funding agencies may enforce accessibility for the digital humanities, as several countries already do. Williams argues that “we should start now to follow the existing guidelines for accessibility and to develop our own guidelines and tools for authoring and evaluating accessible resources” (Williams).

Readers who are blind, have low vision, or are colour blind would have difficulty with this blog. In the name of “universal design,” as espoused by George H. Williams, we need to develop interfaces which blind people can interact with, such as a easily-usable programs which read content aloud. In the case of the visualization itself, perhaps a tool which describes the image in an adjustable amount of detail would be effective. In determining which two colours we should use to represent male and female writers, we decided to avoid the facile and overused pairing of blue and red. However, be cause we wanted to account for colour blind viewers of our visualization, we followed the research of Masataka Okabe and Kei Ito from their paper “Color Universal Design (CUD): How to make figures and presentations that are friendly to Colorblind people.” They caution people against using combinations of red and green and advise that instead, we use magenta or purple with green.

In general, we have tried to make this blog as universally accessible and user-friendly as we can with our technological skills, by writing in an informal voice, integrating emphasis and titles, and including hyperlinks which break up the monotony of reading large blocks of text. Williams argues that ultimately, all technology is artificial, and that there is no natural way to interact with it: instead, as he says, “there is only the model we have chosen to think of as natural” (Williams). Perhaps the best we can do is continue to be aware of our reader and consider the intersecting difficulties or strengths that people have when interpreting this sort of text.

Works Cited

Bingham, Jane and Scholt, Grayce. Fifteen Centuries of Children’s Literature: An Annoyated Chronology of British and American Works in Historical Context.” Nineteenth-Centiry Literature Criticism 52 (1980): 68-69.

Okabe, Masataka and Ito, Kei. “Color Universal Design (CUD): How to make figures and presentations that are friendly to Colorblind people.” J Fly. J Fly, 15 Feb. 2002. Web. 17 Nov. 2015.

Moretti, Franco. “Network Theory, Plot Analysis.” Pamphlet. Vol. 2. May 1, 2011. Print.

Williams, G. "Disability, Universal Design, and the Digital Humanities" Debates in the Digital Humanities 2012

Last updated